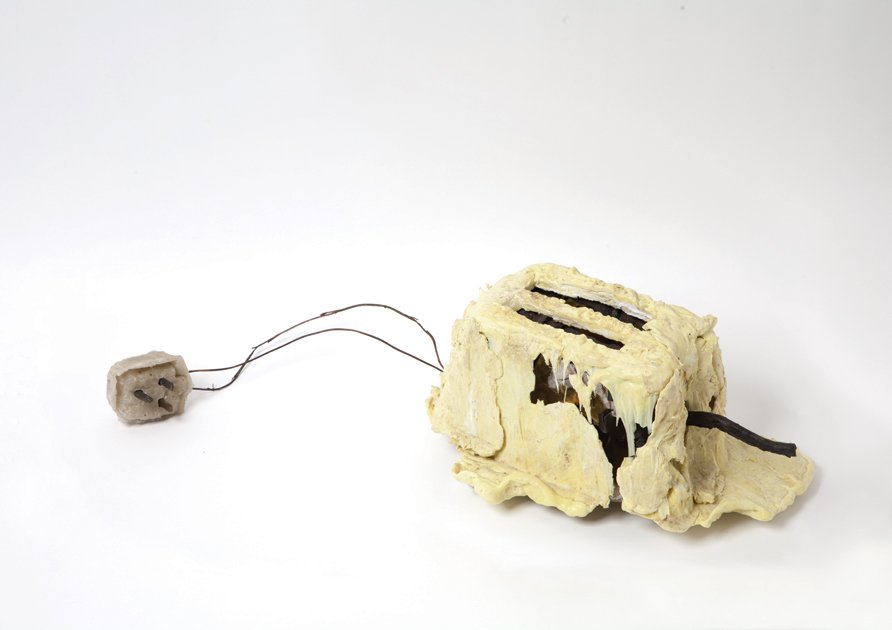

In 2010, a curious man named Thomas Thwaites embarked on an unusual journey. He wanted to build something as ordinary as a toaster—but from absolute scratch. His idea was simple in theory: take apart a cheap toaster, learn how it works, and then recreate every component himself using raw materials. However, what unfolded was far more enlightening than he had anticipated.

The Hidden Complexity of Simplicity

Upon dismantling his store-bought toaster, Thwaites discovered that this seemingly simple kitchen appliance was anything but. Spread out before him were over 400 individual parts, composed of more than 100 different materials, including plastic, nickel, and steel. The sheer intricacy of manufacturing something so commonplace was eye-opening.

Determined to move forward, Thwaites decided to tackle the steel components first. Steel is made from iron, so he reached out to a nearby iron mine and asked for some iron ore. To his surprise, the mine agreed.

But his next challenge was less accommodating. In order to make the plastic casing, he needed crude oil. This time, Thwaites contacted BP, hoping they would let him visit an oil rig and collect some oil. Unsurprisingly, the oil company declined. Undeterred, he resorted to scavenging plastic waste, melting it down, and molding it into the toaster’s casing. The result, however, looked more like a misshapen lump of melted cake than a sleek appliance.

Throughout the entire project, Thwaites encountered similar roadblocks. To produce nickel parts, he melted down old coins. Every new component required him to engage with complex systems that already existed in the world. Reflecting on his experience, Thwaites admitted, “I realized that if you started absolutely from scratch you could easily spend your life making a toaster.”

Why Starting from Scratch Is Rarely the Answer

Thwaites’ experiment, famously known as The Toaster Project, offers a profound lesson: starting from scratch often isn’t the best path to innovation. Yet, many of us fall into the trap of believing that breakthrough ideas must emerge from a clean slate. When a project fails, we speak of “returning to the drawing board.” When we want to improve ourselves, we imagine wiping the slate clean and starting anew.

But genuine innovation rarely works this way. Instead, progress is typically a gradual process of building upon what already exists.

Nature provides a perfect illustration of this principle. Consider the evolution of birds. Many scientists believe that feathers originally evolved from reptilian scales, first serving as insulation and later developing into structures capable of flight. At no point did evolution completely discard existing forms and start over; instead, it repurposed and refined them over time.

Human innovation follows a similar trajectory. The Wright brothers are widely celebrated for achieving the first successful powered flight. Yet their accomplishment was the culmination of knowledge built upon the efforts of earlier aviation pioneers such as Otto Lilienthal, Samuel Langley, and Octave Chanute. The Wright brothers didn’t invent flight in a vacuum—they refined and connected previous ideas into something extraordinary.

Innovation Is Connection, Not Creation

The most groundbreaking ideas are often not entirely original. Instead, they emerge from combining and improving upon existing concepts. Innovative thinkers excel not because they conjure ideas from thin air, but because they recognize patterns, make connections, and iterate on proven foundations.

In reality, a small, incremental improvement—perhaps just one percent better—often leads to more sustainable progress than trying to rebuild from the ground up. This iterative approach allows us to refine and adapt without discarding valuable lessons learned from previous efforts.

Seeing the Invisible Forces Around Us

What The Toaster Project also highlights is how blind we often are to the intricate web of systems that support even the simplest products in our daily lives. When we buy a toaster, we don’t consider the mining of iron, the drilling for oil, or the global manufacturing networks that make its production possible. We see only the final product, not the hundreds of interconnected processes behind it.

This is an important realization when approaching complex problems. Existing solutions have already survived numerous challenges and obstacles. They have been tested and refined by time. Dismissing them entirely ignores the value embedded in their longevity.

In a world where complexity often masks the underlying forces at play, leveraging existing ideas and processes gives us an advantage. Old ideas are not obsolete; they are battle-tested. They represent a foundation upon which we can safely experiment and innovate.

The Art of Iteration

True creativity doesn’t demand that we reinvent everything from the ground up. Instead, it invites us to iterate—to make thoughtful adjustments and improvements to the structures already in place. This approach not only respects the complexity of the world but also increases our chances of meaningful progress.

Thomas Thwaites’ toaster may never have made it into anyone’s kitchen, but his experiment serves as a lasting metaphor for innovation itself: don’t start from scratch—build from what works. In innovation, as in life, iteration is often the smartest way forward.